Interview with the John Locke Foundation’s Jon Sanders

Economist Disputes Validity of Economic Impact Studies, Likens Them to Alchemy

TRANSCRIPT

JON: These developers will come together and produce an impact study saying, “Our project is going to just magically shower your community with money that you know is out there, and all these people are just dying to come to your community, and the only thing that’s holding it back is that the government hasn’t kicked in a little bit more money in tax credits, or grants.” And they’ll tell the commission, they’ll tell the city councilors, whichever, “As soon as it happens, our project is going to just massively increase the investment in the community, in your community. It’s a win win for everybody. We’re gonna make money. You’re gonna make money. People are gonna vote for you.” And so people fall for this and they give you these large studies, so sometimes they’ll be 60, 70, 100 pages long and full of numbers, it certainly seems very professional and it certainly seems very economically done. But most of the time, there’s no actual economics in it.

ILONA: Welcome to All Things Hudson Valley. My name is Ilona Ross. It’s Friday, October 30, 2020, and I’m speaking with Jon Sanders, an economist at the John Locke Foundation in North Carolina. Jon studies the studies that are put together to persuade local governments to give away millions in tax breaks. I’m in Ulster County, in the beautiful Hudson Valley, and here the question is whether it is right to give $27 million in tax breaks to developers of luxury housing. A new agreement would have the developers pay $5 million over 25 years. But how does that stack up against $27 million in tax breaks? Jon wrote an article comparing tax giveaways to alchemy, and that’s some serious alchemy, when $27 million in tax breaks becomes at least that much cold hard cash in the developers’ pockets.

ILONA: So why don’t you tell me a little bit about yourself, your background, your education, and what the John Locke Foundation stands for.

JON: Sure. My background is I’m an economist, and I came into economics by way of actually by being an English major. I think it helps because one of the problems with economists in general is we have a tendency to talk past people or not communicate very well. Economics is a very dry subject, and it gives most people hives. So we try to communicate better, and my background in English I think helps with that. The John Locke Foundation is a free market think tank in North Carolina. Our philosophy is very much like our namesake, but we have a North Carolina claim on John Locke in that he was sponsored by one of the Lords Proprietors under the original colony of the Carolinas and he helped write our first constitution.

ILONA: So, free market. Does that mean libertarian?

JON: To some people as it means libertarian, sometimes some people it’s conservative. It just depends on the speaker, so I like to just say free market because that’s more in line with my personal philosophy.

ILONA: Well, either way it seems that these tax breaks are an issue that bridge the divide between libertarians and conservatives and Democrats and Republicans. So, I’m not sure if you’re familiar with something that we call Industrial Development Agencies. That’s what we have in New York State and they are empowered to give tax breaks. And most tax breaks that the IDAs give are ten years long, and they do not require anybody’s approval. But the Kingstonian is a 25-year tax break, and it requires the approval of three taxing jurisdictions. That’s the Common Council, the Ulster County Legislature and the school district. What is the mechanism that you have in North Carolina?

JON: Well so in North Carolina, we don’t have the IDAs, as you describe them, but we do have special funds set up for the governor to use to give either grants to and these are generally smaller. This is called the One North Carolina Fund where grants are given to corporations to either expand or to move into North Carolina. And then we have Jobs Development Investment grants, which are larger and longer-term tax rebates that generally span 12 years. These can be several millions of dollars, as well as we’ve just recently added what they call a Transformative JDIG, which is Jobs Development Investment Grant, which was created by the legislature a couple of years ago when we were chasing the Amazon and Apple headquarters expansions. Basically, this is very large grants and tax credits that last for decades.

ILONA: You have no mechanism that that requires property tax abatements? Because, see, in New York State, the school district are funded by property tax and you haven’t mentioned anything about property tax just yet.

JON: No, that’s a good point, and the counties and city governments can negotiate their own kinds of other incentives and things.

ILONA: Yeah, I read an article somewhere, it could have been in Good Jobs First — I’m not sure — that said that North Carolina was second only to New York State in the amount of money that is siphoned away from school districts through property tax abatements for economic incentives. What’s wrong with economic impact studies? This is something that I think people need to know about. The things that I’ve learned is that they don’t look at the cost of community services, they don’t look at opportunity cost, they don’t look at time decay, and they don’t look at the best use. So are there any other issues that you can think of that are wrong with them?

JON: After you’ve mentioned all of those, I mean I could say that probably, you know, they use a bad font in their printing maybe. Those are the highlights. Yes. The way this works is, frequently, someone will have an idea in a community. I want to build a new baseball stadium, or I want to, to bring in development. I want to, you know, to bring in a new row of apartment complexes. I want to stimulate jobs here, and no one’s doing that. And so they think, well, we just need to bring a little bit more money to the table. Well, these developers will come together and produce an impact study saying, “Our project is going to just magically shower your community with money that you know is out there and all these people are just dying to come to your community, and the only thing that’s holding it back is that the government hasn’t kicked in a little bit more money in tax credits, or grants.” And they’ll tell the commission, they’ll tell the city councilors, whichever, “As soon as it happens, our project is going to just massively increase the investment in the community, in your community. It’s a win win for everybody. We’re gonna make money. You’re gonna make money, people are gonna vote for you and cheer you on the streets. It’s just going to be wonderful.” And so people fall for this and they give you these large studies so sometimes they’ll be 60, 70, 100 pages long and full of numbers, it certainly seems very professional and it certainly seems very economically done. But most of the time, there’s no actual economics in it. They’ll use proprietary software that you just plug the numbers in and fiddle with them. You don’t need an economist who knows things about opportunity costs, who knows things about the law of diminishing returns. You don’t have to worry about all that, you don’t have them say, you know, that money could have been used better elsewhere, or what other people do with it. None of those things. So it’s all win win.

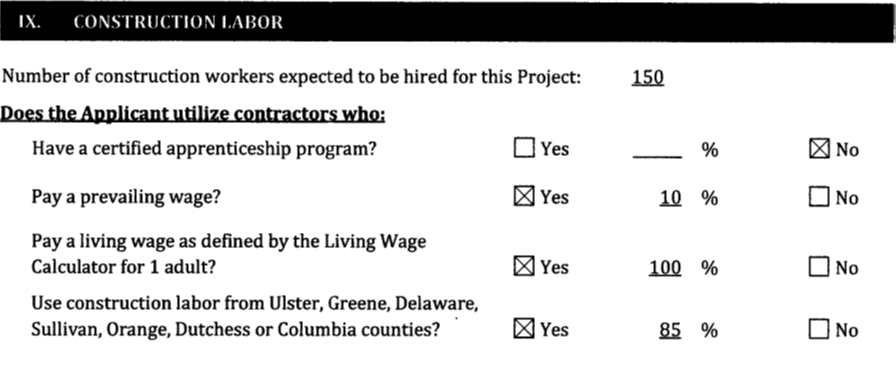

ILONA: Okay, so let’s talk about opportunity costs. There was a wonderful article on your site and it was entitled, “What’s Missing in Economic Impact Studies?” The answer: “Economics,” and it then goes on to, somewhere, somewhere in the article it quotes the 19th century economist Frederic Bastiat, who I presume was French, and he famously pointed out, “There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one. The bad economist confines himself to the visible effect. The good economist considers both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.” So, I called it time decay and you called it the Law of Diminishing Returns. It’s good to know that that’s the proper word for it. The Law of Diminishing Returns, because I noticed in it all the fancy literature and pie in the sky numbers that the developers produced, they never gave timeframes. Somehow this development, this multi use luxury housing development is going to produce 359 jobs, and that that’s construction jobs. The numbers change by the way all the time, but they have, they had a slide where it’s 359 jobs. They don’t say what time period it’s going to take place over, they talk about huge amounts of tax revenue that’s going to be generated.

[In fact, the number was 357, not 359. That’s what developer Joseph Bonura told the Chamber of Commerce on August 12. The application to the IDA says 150 construction jobs will be created. The website, however, says 100 temporary construction jobs will be created. Snapshots of all these statements are posted at the bottom of the transcript of this podcast. Never is it specified which are so-called spillover jobs, what multipliers have been used, or for how long these jobs will percolate through the economy. If you’re interested in learning about multipliers, the Bureau of Economic Analysis put out an example that is linked at the end of the transcript.]

ILONA: What can you tell me about opportunity costs?

JON: The opportunity costs question is really the biggest question in these studies. Going back to my English background, opportunity cost is Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.” All right. You take one path and that makes all the difference. You don’t know what was down the other road. So in economics, the opportunity cost is the foregone benefits from the choice that you’ve made. And it doesn’t matter. It could be anything. In this, in this context, it is the choice to direct tax money to this developer, as opposed to other alternate uses of that tax money, or also letting people keep that money.

ILONA: So that’s interesting because in this case, first off, one of the developers owns the land that this development would take place on. So he’ll find another use for it. And what they say is that, if this garage and multi use development doesn’t get done, nothing is ever going to happen. They tell you that it’s “but for” the tax PILOT they can’t do it. And they make it sound as if this spot is the last place in North America to build a garage on, and it’s just going to remain fallow forever. And of course that’s not so. So they don’t want to talk about the lost opportunity cost.

JON: So you say you have, you say you’re not following the economics of it, but you have very good insights into that. But the whole idea of the “but for” is essentially to make the argument that this would not happen at all unless we got this tax break. So, if, if the project would take place, and these guys are just rent-seeking, which is another economic term, it’s they’re just trying to collect as much money that they can get for something they’re already going to do, then there’s no benefit at all accruing to the community and it’s all cost.

ILONA: Let’s talk about time decay and I called it time decay and you called it the Law of Diminishing Returns. What exactly do you mean by that?

JON: I’m just basically suggesting that the benefits that are supposed to accrue from this project will not be a constant over time. People are going to see other opportunities, other choices. You mentioned the construction jobs for example and those go away as soon as the thing’s built. And then whatever tax that the government will get from the those 300 I forget how many you said employees working in the construction, that will dry up.

ILONA: They say there’s going to be spillover construction as a result of it, they say, they talk a lot about spillover jobs, but by the same token, I actually spoke with an economist whose organization sells programs such as these, and he got very snippy with me when I asked him if they’ve ever checked their application for accuracy over time. And he replied that it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to track that dollar through time. But, you know, they’re probably making hundreds of thousands of dollars selling these programs. So, I, you know…

JON: Oh, and it depends on what they’re selling too. If they’re selling to their clients glossy presentations that will persuade city councilmen and county commissioners to go along with the project that they’re selling, they don’t need to worry about whether or not it actually is true five, ten years down the line. They, they are helping engage in selling the project to the politicians.

ILONA: Yeah, and then the politicians forget about it after a little while. This is true we have… there are stories in Ulster County of people getting huge tax breaks and they hire one person. There’s another instance in Ulster County, it’s with the Holiday Inn right outside of Kingston on 9W, and they stiff the school district about $330,000 every year. And I took a look at who owns the Holiday Inn, and it turns out it’s owned by Intercontinental which is a UK based multinational corporation, and the largest shareholder is JPMorgan Chase. And so it’s really good to know that the 46% minority schoolchildren of Kingston are subsidizing Jamie Dimon and his fellow paupers. Yeah, there’s a fair amount of that. That’s one of the more egregious examples but even so…

Can you tell me about these programs that are used? I took a look. They have a lot of a lot of acronyms. There’s IMPLAN, there’s… Oh my gosh, why don’t you tell me a little something about them, and are they any different and are they useful at all?

JON: Okay, yeah. So you mentioned IMPLAN. There’s also something called JEDI. There’s something called REMI and there are several other varieties of these. They’re input output economic impact modeling software, proprietary software that companies sell. And what you can do with them is you take the inputs. They normally have some numbers that you can fiddle with the, the numbers and the assumptions and produce an output number of, here’s how much my organization, my company, my development, my baseball stadium, whatever, will produce for the economy of your local government. The problem with these models, for that use, is that there’s no way to generate a negative number. There’s no opportunity cost factored in. A lot of what in business terms would actually be costs are counted as benefits. So if you have to hire people, labor, labor doesn’t count as a cost. Labor counts as a benefit. If you have to buy a lot of equipment, your capital doesn’t count as a cost, it counts as a benefit. So, any spending at all counts as a benefit. But that’s not how economics works and that’s not how life is.

ILONA: Oh my gosh, doesn’t FASB, don’t any of the accounting organizations come down on these companies for putting assets, for putting assets on the liability side or liabilities on the asset side?

JON: They’re very slick about it because they say look, it’s all the spending that’s going on in your community. Look how many people are going to be employed by this and they’re going to be paying taxes and, oh well, then let’s get tax money to them. Okay. But if you’re going to look at it from that angle then you have to compare tax revenues coming in tax and revenues coming out, if we’re looking at it from the societal, the society side of it, as opposed to what’s best for the company. And that’s where these things fall apart.

ILONA: I’m still blown away by the fact that costs are turned into benefits. That’s some serious alchemy. I believe it was, was that an article of yours, where you said it was full of alchemy?

JON: Yeah, I was, I was writing recently about one of these deals in North Carolina where we are going to give a company. I can’t remember the exact numbers but like 4 million they were going to agree to invest 3 million, and somehow, it was gonna turn into 600 million.

ILONA: Yeah that’s some serious alchemy.

JON: I call it a gullibility test.

ILONA: Okay. Wow. So, so in other words, you can input any numbers you want the, the numbers don’t necessarily have to be accurate. And then on top of it, you can turn costs into benefits, and you can use multipliers that may or may not be true. And there’s no sense of the Law of Diminishing Returns. So, in essence, are these programs any better than snake oil?

JON: In my opinion, generally not. And I know I’m a little down on these things. Yes, I’m a little bit cynical about them. But the whole assumption is really at the end of the day, investors whose job it is to find ways to make money are not investing in these projects. And politicians who may have many other skills, but making money is possibly not one of them, at least not in the private sector… And we’re to believe that they’ve come up with the bang up idea that’s going to make scads of money for the community and for the company that no one else has come upon and all it takes is a little bit of a tax refund. And my reaction to that is, okay, what you’re really saying is our taxes are too high for investment. So, to me, as a free market economist, my first thought is, lower taxes.

ILONA: I saw out of George Mason University a study that said that if Albany was not so free with its economic incentive largesse, the state corporate tax rate could be reduced by 93%. That’s a pretty spectacular number. I mean you’d still be paying your federal taxes, but can you imagine that?

JON: That is a very large number. But, I mean, it gets at the point where essentially when you bring in a new developer, and you give them a tax cut because it’s good to have the new developer, and we’re excited about the new jobs, you’re making people who are currently there and businesses who are currently there fund that.

ILONA: Yeah. It’s not fair to other landlords, it’s not fair to other small business people.

NARRATION: Earlier in the podcast, Jon talked about fiddling with the numbers fed into these input/output programs. Certainly, there was a lot fiddling with the numbers that were used as inputs to produce the report from the National Development Council on the Kingstonian multi-use development. In case you’re not familiar with how this report came to be, the background is that Ulster County commissioned a so-called independent review of the economic impact numbers that the Kingstonian developers have been touting. But the National Development Council fiddled with some numbers and blindly accepted other numbers provided by the developers. For example, the NDC accepted the notion that there would be 277 new parking spots, and then they valued that supposed benefit to the community at more than $10 million. But that’s a gross exaggeration, because there already is a parking lot, and even using the developer’s figures, at most 139 new spots would be made available. And even 139 new spots is a gross exaggeration, because anyone who’s analyzed the parking knows that the real number of new spots attributed to construction of the garage will be anywhere from a loss to maybe several dozen new spots. Another trick the developers used was to fiddle with a kind of number known as net present value. You can input different discount rates to produce the net present value that you want, and those numbers were massaged to produce the result that the developers want. In short, the developers want to prove that there is a net benefit to the community, and even the NDC report itself says that its goal is to show there is a net benefit. It doesn’t matter if there really is or isn’t a benefit, just so long as you can fiddle with the numbers enough to show one. For a detailed look at these and more examples of numbers fiddling, check out the Hudson Valley Vindicator — that’s HVvindy.com — for the article entitled Friends With Benefits that explains some of the tricks with numbers that were used to prove that this project provides a net benefit to the community. It should come as no surprise that a close look at the numbers shows there is NO net benefit.

ILONA: How do I say, it’s just smoke and mirrors and it’s just a lie.

JON: I think that’s how you say it.

ILONA: So it’s so hard for us non economists to know where to begin and to know what to say. What words of advice do you have for the people of Ulster County and the people of Kingston, and mostly the legislators and the school board members who have to vote on this thing?

JON: Well, I’m sure there are plenty of good economists around Ulster County and in Ulster County that could be consulted. I would talk to some economists and ask them about the plan, maybe see if you can get somebody to testify and talk about it. For a company to say, we would like to use this land, but we really can’t do a project and make money on it, unless you give us a whole lot of money, in a way it’s kind of like Blockbuster Video coming in and saying, you know, man, we got a great we got a great business model and who would really work. You just have to guarantee that people still use VHS and that you will send people our way.

NARRATION: The way small businesses are folding throughout New York State, this analogy might very well apply to the eight or nine thousand square feet of retail space that the developers are planning for the Kingstonian.

JON: And then there’s other companies out there that maybe we don’t know who they are, but down the line, could make much better use of the property in a way that would benefit the community through taxes, that would benefit the community from providing value to that property and providing something that people really like. But that would be prevented if the government is paying somebody who is providing something that they couldn’t make money on otherwise, to build there.

ILONA: Yeah. Do you teach?

JON: I have taught as an adjunct at North Carolina State University and at the University of Mount Olive, both of them in North Carolina. And I’ve been working as an applied economist for many years.

ILONA: Now Jon is at the John Locke Foundation, where he works as a regulatory economist and is also the research editor.

ILONA: What exactly is a regulatory economist and what is an applied economist?

JON: Basically I, my my work is I look at regulatory policies. So in that sense, I’m a regulatory economist. There are many different flavors of being an economist. Mine is more generalist. So that’s why most of my work is applying economic principles, so I say applied economist. And then I work in regulatory policy for the most part, so I say regulatory economist.

ILONA: Okay. All right. All right. Well, this is great, listen Jon, thank you so much. This was wonderful. It was just one more, one more voice to add to the chorus.

JON: Well, that’s what I, that’s kind of what I like about it is because these issues are not Democrat versus Republican or Right versus Left. These issues are more the insiders versus the people. And I like those issues because I think at the end of the day, that means the people can come together and it’d be nice because we can actually get along for something, and make real substantive change, but it’s also difficult because the connected insiders have all the money and they have all the time. And they’re the ones that stand to benefit the most from winning.

ILONA: Well, at least we can inform the public, and voices like yours are crucial.

JON: Thank you so much. It’s been really wonderful talking with you.

ILONA: Likewise. Have a good one.

ILONA: Thank you for listening. As you’ve heard, the real alchemy is when $27 million in tax breaks becomes at least that much profit in investor pockets. We know this because of financial metrics such as the 13% rate of return to the developers. This is money that would have gone to local governments, mostly to the school district. At a time when NY Governor Andrew Cuomo is threatening to cut school budgets by 20%, is this tax break the right thing? The eyes of the public are opening to the damage caused by corporate welfare, whether it’s the swamp inside the Washington DC Beltway or the swamp in small towns across America. Pundits speculate that it is disgust with this kind of greed and corruption that has led to the rise of outsiders such as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. If you haven’t voted, please do so, and in the meanwhile, stay safe.